Editorial from the February 2018 issue of Anglican Life:

And just like that, we’re back to the shortest month of the year, and often one of the coldest and most miserable for us in Newfoundland. February is the month that I always use in my examples of horrible weather, as in: “Well that’s a nice long driveway in the summer, but just think of shovelling it in February!” While we started winter months ago, we had the warm cheer of Christmas, and then new year and its resolutions. But now February has set in, and it’s cold, and it’s still dark.

But we have a lovely bright warm spot in the middle of the month with Valentine’s Day. As a kid, that meant making a “mailbox” in school from an old cereal box or something, and then the excitement of passing around Valentines to our friends, and getting them in return. As we get older, there is the romantic pressure of the day—the expected grand gesture or gift. But of course there must be more to the story of Valentine than the gifts, the fancy suppers, and even more than the funny little cards that we gave to our classmates.

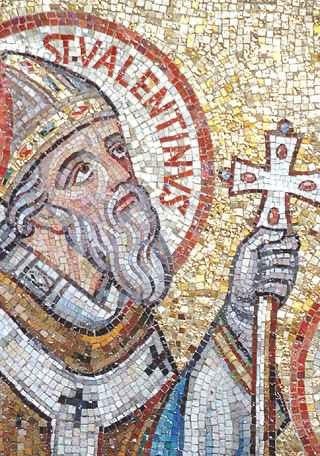

Actually, there is very little that we know for certain about St. Valentine. We know that he existed in third century Rome, and that he was martyred for his faith and buried in a cemetery that is north of Rome. The name “Valentine” itself was popular at the time, and comes from the word valens, which means worthy, strong, or powerful. There are about a dozen saints in the Roman calendar who are venerated, and who share this name.

The most common version of the legend of this St. Valentine is that he was the Bishop of Terni, Narnia, and Amelia in central Italy. While under house arrest, a Roman judge questioned him on the legitimacy of Christianity and the faith in Jesus Christ. Valentine was challenged to restore the sight of the judge’s daughter through the power of prayer, and if he could do that, the judge would do whatever Valentine asked. So Valentine put his hands on the girl’s eyes, prayed, and her sight returned.

The judge asked what he should do in response to this miracle, and Valentine replied that all of the idols that were around the judge’s house should be destroyed, that the judge himself should fast for three days, and he should then be baptised a Christian. The judge agreed, and also freed all of the Christian slaves that were under his authority—he, his family, and all of the members of his household were baptised.

Valentine was later arrested again, and was sent to the emperor Claudius Gothicus himself. The emperor liked Valentine, but grew angry when Valentine tried to persuade him to be baptised too. Claudius insisted that Valentine should renounce his faith or else be beheaded. When Valentine refused this request, he was executed on February 14th, 269.

There are many other legends of Valentine, and many reasons given for his later association with romantic love, including theories about Valentine’s Day being an attempt to take over the pagan holiday of Lupercalia (celebrated mid-February in Roman times). Many of these legends were actually invented in 14th century England, notably by the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, and are now dismissed in serious academic circles. However, in the almost complete absence of any real stories of Valentine, there seems little harm in taking time in the middle of a cold and dreary month to think about loved ones, to celebrate important relationships in our lives, to cut out red cardboard hearts, and maybe even to eat a bit of chocolate. The saints are there to point us to the love of God, and in many ways, regardless of the truth behind his many legends, St. Valentine reminds us all to love, and that is fundamental to our lives as Christians.